21 January 2013

The Hymnbook Archive of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) holds perhaps the world's most important collection of utilitarian Christian literature, making it an essential resource for scholars. Hymnbooks reflect history in a unique way. Professor Dr. Hermann Kurzke invites us to take a tour through the centuries.

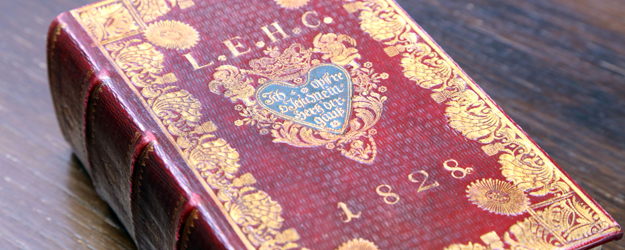

The metal drawer slides open to reveal books. Old, visibly battered books. "This one here is something special," says Professor Dr. Hermann Kurzke, taking out a thick volume. "I bought it from a demolition expert, a blue-collar fellow who had been collecting hymnbooks in his garage. Unfortunately it has burn marks."

Kurzke flips open the first page. "Berlin 1700" is printed there, with an artistic engraving of a harp. "The image for the Psalter." And a dove. "This represents the Holy Ghost." Water flows from a harp, transforming into a river that then becomes part of a map. Germany becomes visible, with a blossoming tree growing from it, and France next to it with the withered skeleton of a tree. "This is a reference to the Huguenot wars." For French Protestants, it was a matter of life and death.

What the Hugenots were singing

"This is the Lobwasser Psalter, a book that actually goes right back to Calvin," Kurzke explains. "His Protestant Reform Church banned many pleasure activities, such as reading novels, for example, or singing hymns during church services." It was considered that only passages taken directly from the Bible were suitable for singing. So the Huguenots hit on the idea of using the psalter.

"Using the Latin Bible as the go-between, the passages were recomposed into rhymed strophic songs." The project was ambitious. The work sought to encompass 150 different melodies and 150 different strophic forms. "It became a compendium of different forms of meter. Lobwasser then translated it into German in the 16th century." The influence of this work was massive. The clever new formal elements established precedents.

Hymnbooks from four centuries

Hermann Kurzke is visiting the Hymnbook Archive that he originally founded on the campus of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. The Professor of Modern German Literary History has officially been retired since 2005. "But I stop by here quite a bit."

"Weekly," adds Dr. Christiane Schäfer with a smile. She curates the archive together with Hermann Kurzke's wife Marle. Together they are overseeing a collection that has come to hold roughly 4,000 hymnbooks. It has developed into a unique research center in this field, probably the only one of its kind.

The archive is housed in a humble residential house on the JGU campus. A five-room apartment has been reconfigured with rows of shelves to house the hymnbooks from four centuries. There is also space for researchers to work. Computers have been placed on the old office desks. The original living room is now a seminar room. Upholstered chairs stand around the dark wooden table.

Lots of research in the archive

"We're satisfied," Kurzke says, "even if we're constantly running tight on space." Some 300-400 hymnbooks are added each year. Many of these are gifts. The budget is tight, but when it comes to third-party funds the archive is well positioned. It is organized as a so-called Interdisciplinary Work Group at JGU and significantly contributes to research in its field. Its own series of journals, Hymnologischen Studien, already encompasses 24 volumes.

All of these facts slip into the background, though, once Kurzke begins his tour. It's hard not to be swept up when he picks up one of the treasures and starts talking about it. Those who consider hymnbooks to be little more than cultural footnotes are disabused of the notion in a highly captivating way.

"From a cultural-historical standpoint, hymnbooks are an enormously fertile medium. Millions and millions of copies were printed. Their power is much greater than the poetry of someone even like Clemens Brentano – even if I personally am impressed by this works." Hymnbooks reach all social classes. And they are subject to constant revisions. Over the centuries, the songs contained therein have always been reworked, shortened, lengthened, adjusted to conform to the zeitgeist of the time. Sometimes pieces were excised to make room for others.

Faith is not a constant

Under the Nazis, for example, those in power attempted to eliminate references to all things Hebrew. Worshipers at church services would have searched in vain for any references to "Israel" or a "Hosanna." "The faith reflected in the hymnbooks is not constant. Each generation reconstructs it in its own image."

A present, a standardized Gotteslob hymn collection is being hammered out for the Catholic Church. This will be a hymnbook that will be used throughout the entire German-speaking world – and the Mainz Hymnbook Archive is an active participant in the process of creation. "Some 3,000 persons within Germany are involved in this project," Kurzke explains. "There are disputes over each and every hymn, but what will emerge at the end is a relatively pluralistic product. We're applying our influence to try to bring back old texts."

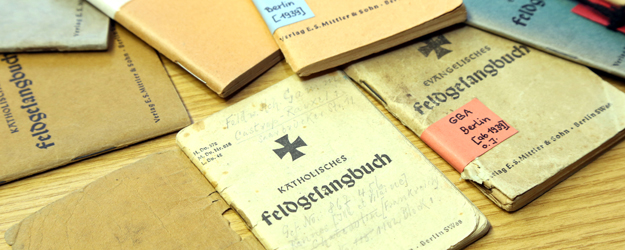

And then the literature expert reaches into the shelf again to tell us more about one of his treasures. Small-format booklets emerge from a gray slipcase that Kurzke has assembled himself. "A Catholic field hymnbook like this fits into the breast pocket of a uniform." Kurzke opens a worn copy from 1939. "You can see someone wrote in prayers in pencil here." A pious soldier, it seems. "I imagine him at the gates of Stalingrad." Yet, the professor notes that the tone of the repertoire of hymns inside is disquieting. "God, who made the iron grow, desires no servants ..."

Migration and church songs

"Am I interrupting?," asks Professor Dr. Ansgar Franz of the Faculty of Catholic Theology as he pops in. He has brought lunch with him. Sandwiches are soon placed out on the dark seminar table. The talk turns to future projects.

"We want to learn more about the migration within Europe during the world wars," Franz explains. He's thinking of people from the eastern parts of the German empire in particular. Such as the 600,000 people who left what was then Breslau and is now called Wrocław in Poland. "The songs in the hymnbooks were part of their identity." But what became of the cultural heritage of the Germans of Breslau? Did they carry it with them to their new homes? Did anything of this culture remain in old Breslau? What has been lost, what has survived? Hymnbooks in this case become something of a litmus test for literary history.

And then the last of the sandwiches are devoured. Kurzke returns to the shelves. He pulls out a hymnbook, a small black one with worn corners. He opens it. "Now this here is something really interesting." The next story awaits.